Scientists may have identified a way to naturally regulate blood sugar levels and sugar cravings in a similar fashion to drugs like Ozempic.

In mice and humans, the key to unlocking this natural process was found to be a gut microbe and its metabolites – the compounds it produces during digestion.

By increasing the abundance of this one gut microbe in diabetic mice, researchers led by a team at Jiangnan University in China have shown they can “orchestrate the secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1”.

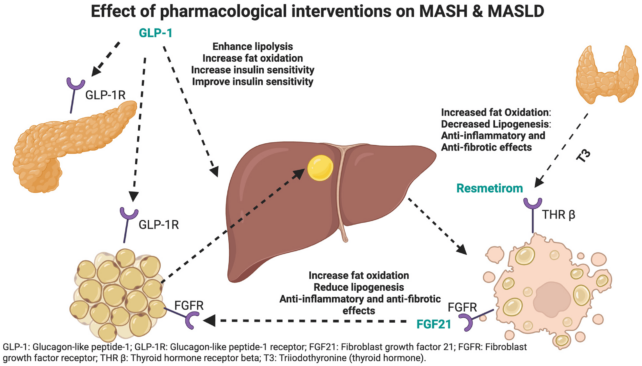

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) is a hormone that is naturally produced by the body and which helps regulate blood sugar levels and feelings of fullness. GLP-1’s release is stimulated by certain foods and gut microbes, and its mechanism of action is mimicked by drugs like semaglutide (the ingredient behind Ozempic).

People with type 2 diabetes typically have impaired GLP-1 function, leading to issues with blood sugar control, which is why Ozempic and other GLP-1 agonists work as treatments.

These drugs mimic natural processes in the body, and while they have proved very effective, some researchers want to figure out how to get the body to produce more GLP-1 on its own.

“A growing body of research has revealed that our cravings for dietary components originate from signals sent from the gut, a key organ in transmitting dietary preferences,” explain the authors.

“However, which genes, gut flora, and metabolites in the gut microenvironment are involved in the regulation of sugar preference is currently unclear.”

The new research suggests gut microbes like Bacteroides vulgatus and their metabolites may help shape a person’s sweet tooth.

In experiments, if mice could not produce a gut protein, called Ffar4, the researchers found the gut colonies of B. vulgatus shrank. This, in turn, decreased the release of a hormone called FGF21, which is tied to sugar cravings.

In studies of mice taking GLP-1 agonists, researchers have found the drugs stimulate FGF21.

Meanwhile, in humans, some studies suggest that those with genetic variants for the FGF21 hormone are about 20 percent more likely to be top-ranking consumers of sweet foods.

In a blood analysis of 60 participants with type 2 diabetes and 24 healthy controls, the researchers in China found that Ffar4 mutations, which reduce FGF21 production, are linked to an increased preference for sugar, “which may be an important contributor to the development of diabetes.”

What’s more, the gut microbiome could be a key mediator of that process.

Sure enough, the research team found that when mice were treated with a metabolite of B. vulgatus, it boosted GLP-1 secretion, which then also triggered the secretion of FGF21.

Together, this meant more blood sugar control and fewer sugar cravings in mice.

Whether the same will extend to humans remains to be seen, but the authors claim their study “provides a strategy for diabetes prevention.”

The study was published in Nature Microbiology.

Source link