Instead of chilled glasses and champagne bubbles to ring in the New Year, how about gassy geysers and frosty avalanches? That’s exactly what you can expect as the Martian New Year begins on the Red Planet with the onset of spring across its Northern Hemisphere.

The term “walking in a winter wonderland” on Mars consists more like sprinting across the surface, having to dodge the crash of cliffsides and explosions of carbon dioxide. Unlike our northern hemisphere on Earth, on the Red Planet, the new year starts off with the beginning of the spring season. The Martian New Year began on Nov. 12, 2024, and spans for 687 Earth days, with the temperature starting to rise and quite the shift in season from winter to spring.

“Springtime on Earth has lots of trickling as water ice gradually melts. But on Mars, everything happens with a bang,” Serina Diniega, who studies planetary surfaces at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, said in a statement. “You get lots of cracks and explosions instead of melting, and I imagine it gets really noisy.”

The atmosphere on Mars is very unique compared to on Earth. For example, when the ice melts the liquid does not form puddles and pool on the surface; instead, sublimation takes place which switches the solid ice directly into a gas. The abrupt shift can be quite violent, as both dry ice (composed of carbon dioxide) and regular ice (made of water) become much weaker and begin to break.

Since we are not able to witness this first-hand on Mars, scientists rely on NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) to be their eyes to track these changes. The Red Planet has been home to MRO since it launched in 2005, and it is equipped with different tools that provide images and observations from the surface.

“Chance observations we get are reminders of just how different Mars is from Earth, especially in springtime, when these surface changes are most noticeable,” Diniega said. “We’re lucky we’ve had a spacecraft like MRO observing Mars for as long as it has. Watching for almost 20 years has let us catch dramatic moments like avalanches.”

Take a look at some of the different phenomena scientists have observed or were able to recreate from data during the Martian springtime, thanks to instruments like MRO’s High-Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera.

Frost avalanches

As the temperature starts its seasonal climb, chunks of frost composed of carbon dioxide begin to break apart and crash to the surface. This process was captured on camera by HiRISE in 2015, when a 66-foot-wide (20-meter-wide) block broke off and was photographed mid-air crashing to the ground.

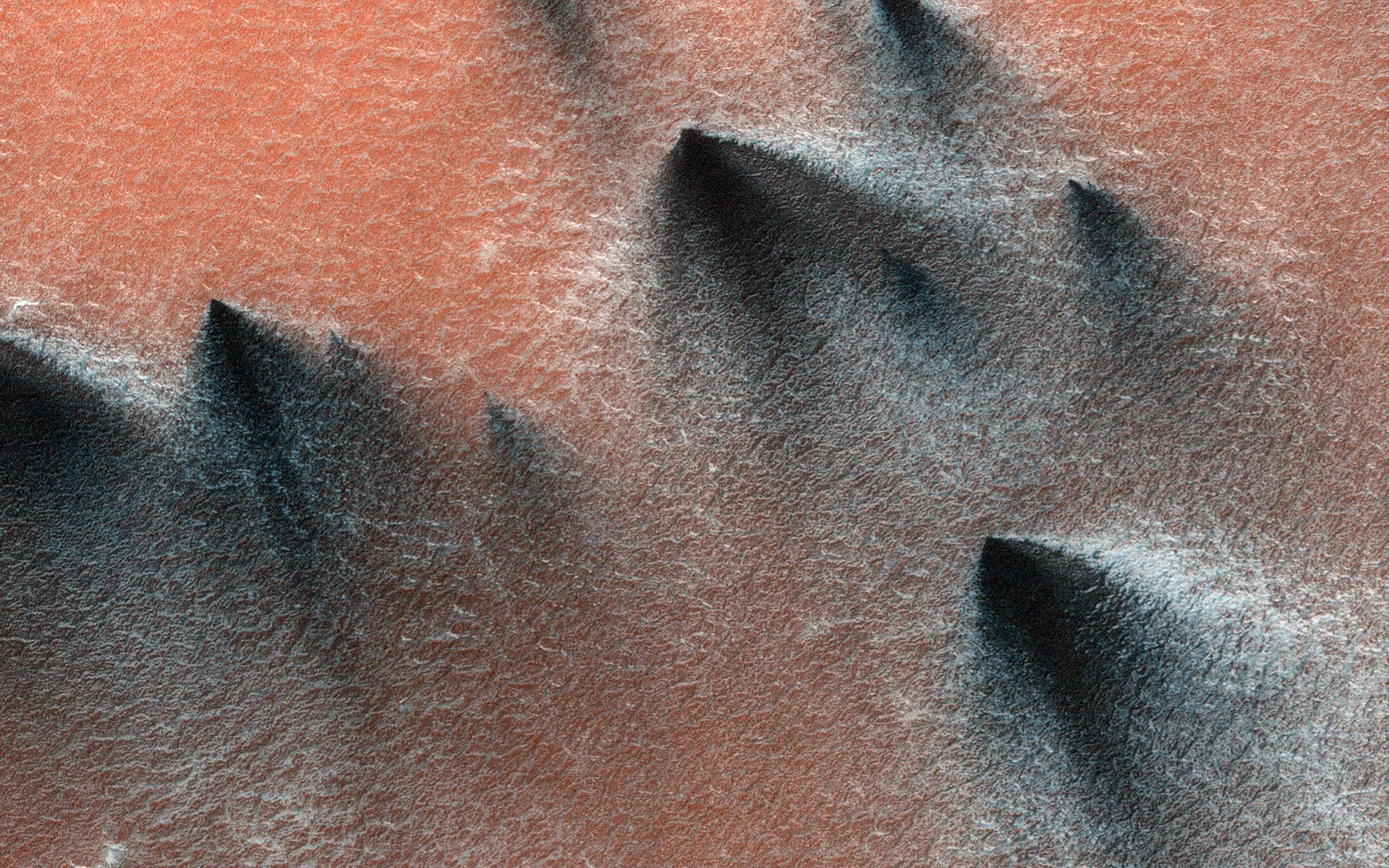

Gas geysers

Imagine geysers in Yellowstone firing up water into the sky, only on Mars, they contain dark debris from under the surface carried up by bursts of gas. As the sun turns the ice into gas underground, the build up gets so powerful that it eventually fires up dark material into the air, leaving behind dark fans on the Martian surface.

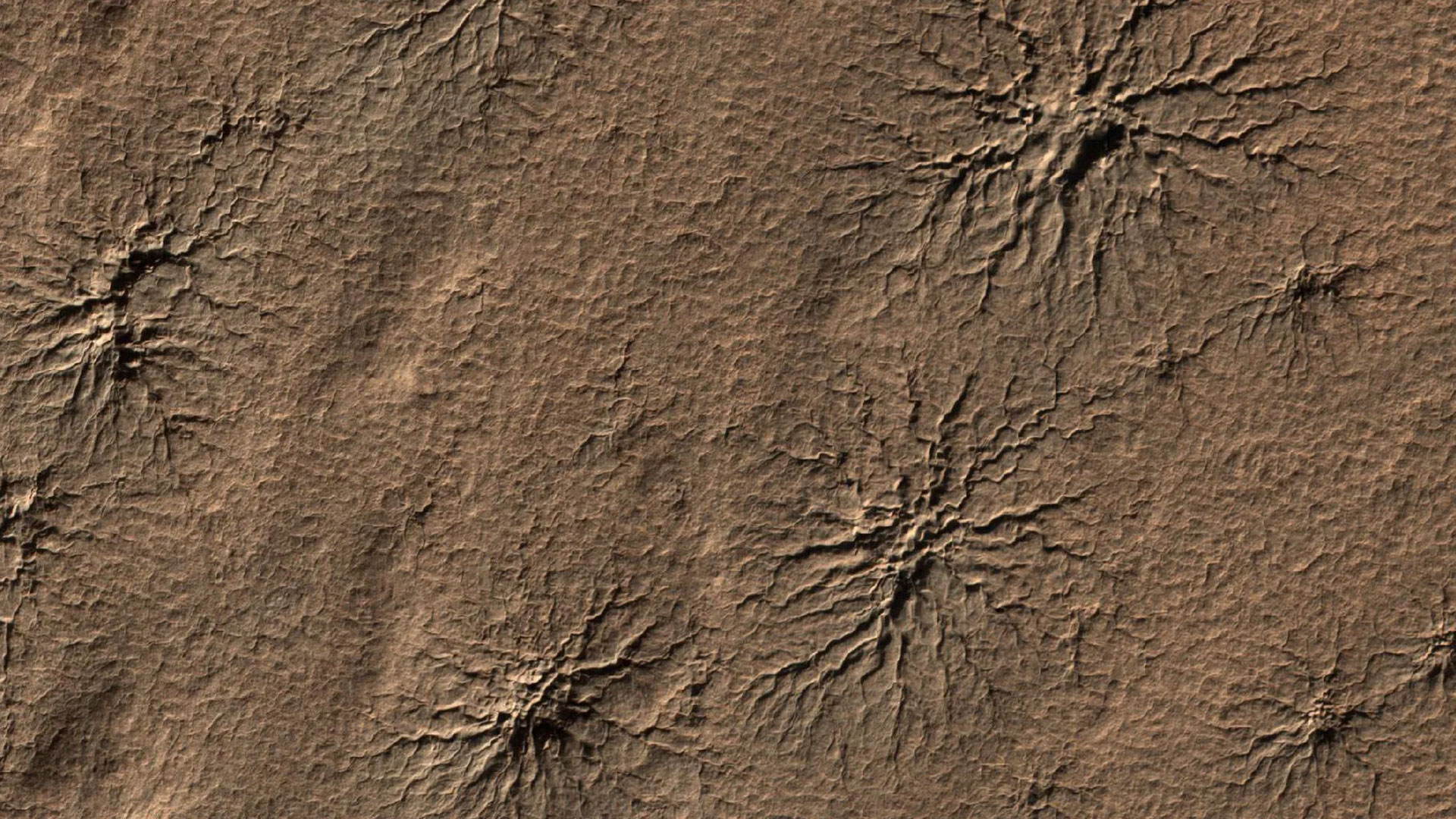

Surface “Dirt” Spiders

It might not be as scary as it sounds, but it certainly might look that way from space! Using a modeling at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), researchers were able to recreate what it would look like on the surface after sublimation takes place with the ice near some of the northern geysers – which resembles big spider legs!

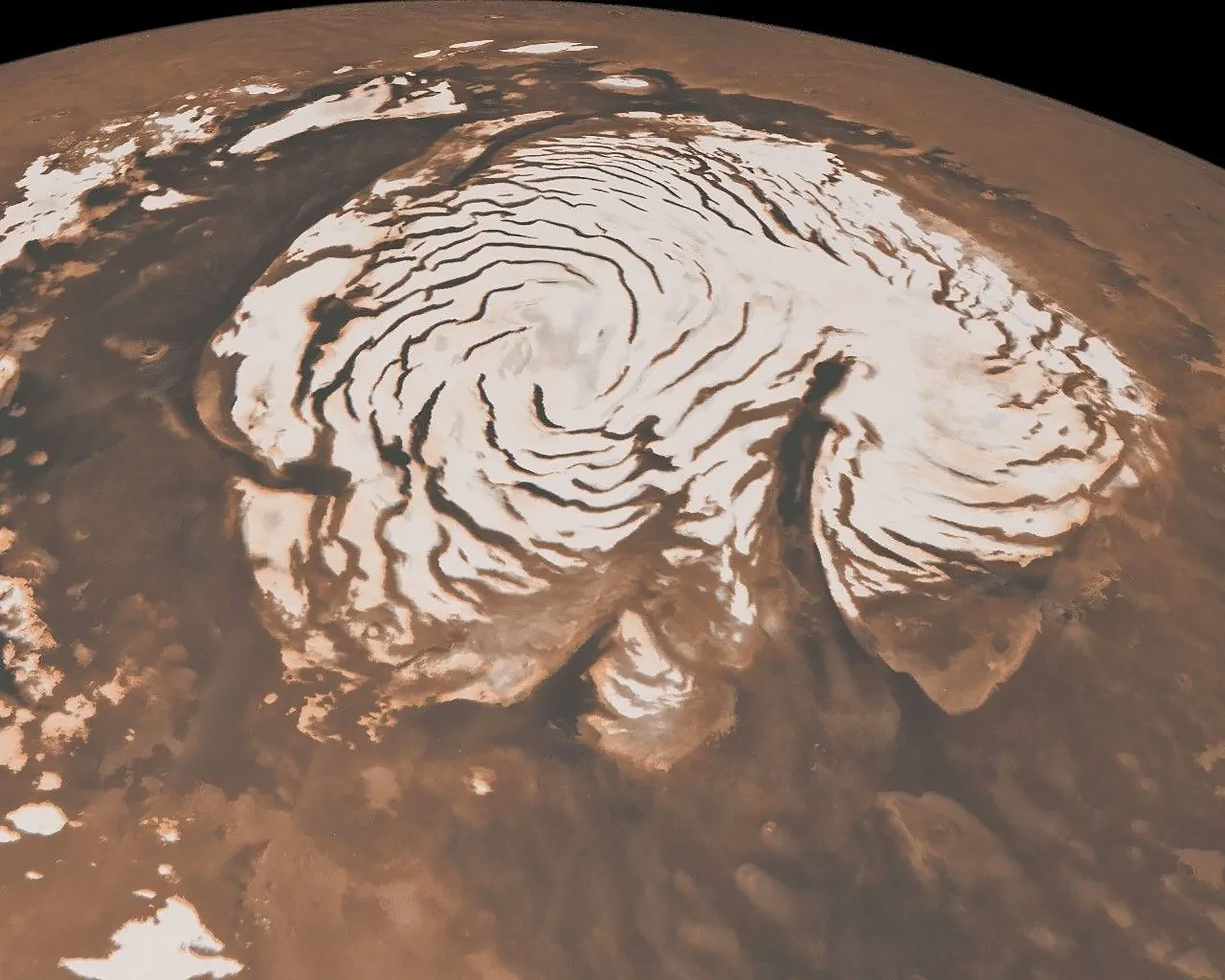

Wild Winds

Did you know at Mars’ north pole, there’s an ice cap in the springtime that’s as big as the state of Texas? As warm, strong winds whirl across the region, deep troughs are carved out as the ice thaws. As a result, a swirling pattern takes shape across the ice cap from above, seen here by NASA’s retired Mars Global Surveyor.

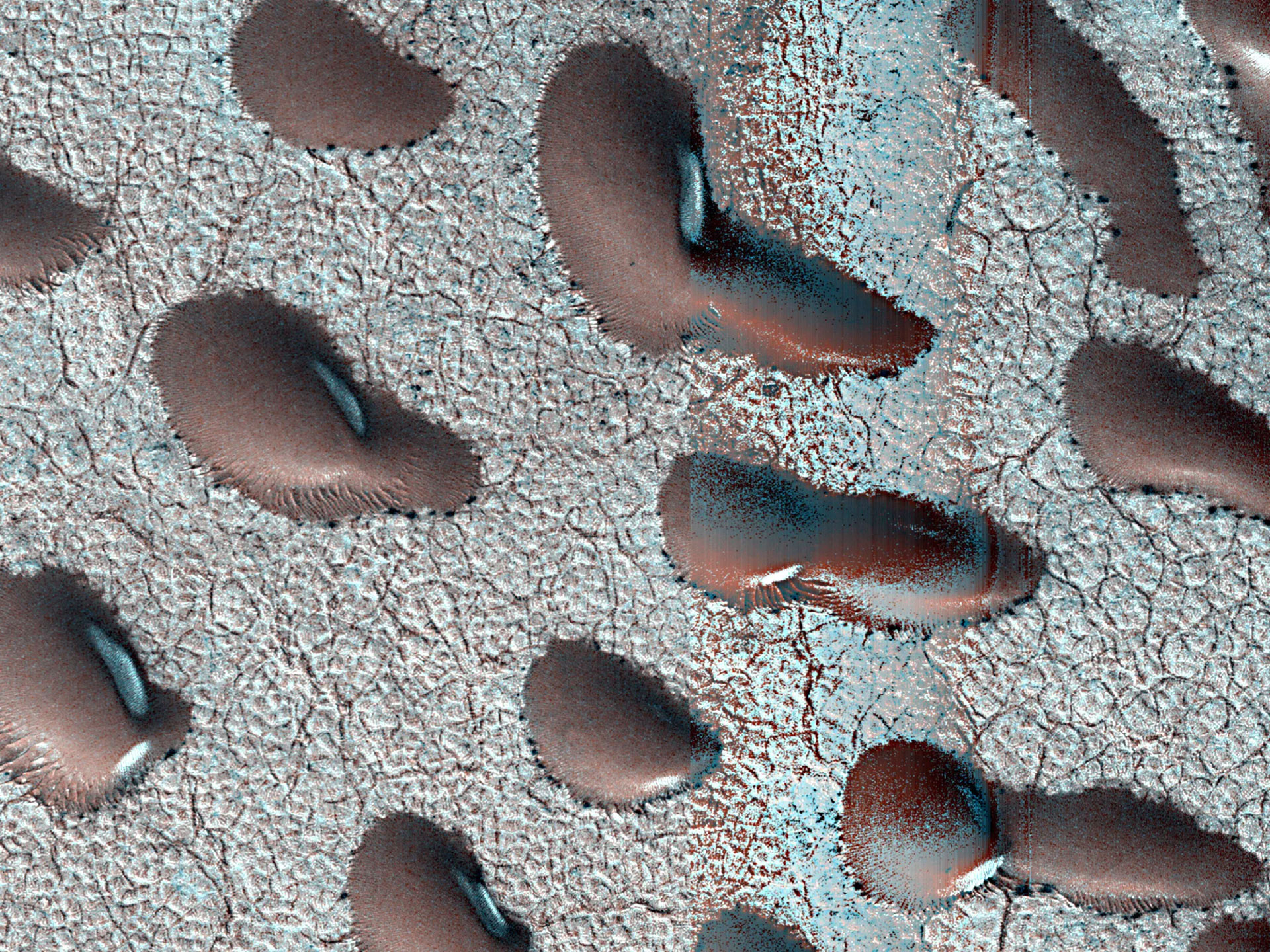

Drifting Dunes

Another fantastic sight to see during the springtime on Mars is the reshaping of its sand dunes by the same warm and wild winds that impact the north pole. The Martian dunes are created and migrate as the amount of sand grows on one side just as it’s removed from the other by the wind.

In the wintertime, carbon dioxide frost forms over the tops of the sand dunes, freezes, and holds them in place until the spring thaw allows them to move again.